HARVARD GAZETTE ARCHIVES

Ottoman Calligraphy at the Sackler MuseumBy Lama Jarudi '00

Special to the Gazette

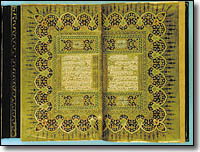

This 1905 work by Ottoman calligrapher Haci Nazif Bey is just one of the splendors on display in the Sackler Museum's "Letters in Gold" exhibit. |

In the Ottoman tradition, calligraphy was always passed from hand to hand, master to apprentice. Before they received permission to create and sign independent work, apprentices – following a practice known as taklid, or imitation – spent many years copying practice sheets penned by their masters. During this long and laborious training process, even the poorest of masters expected no remuneration from their students.

The calligraphy that the Ottomans produced had its origins in the early days of Islam, when Muslims began to search for the most elegant way to pen the sacred words of the Qur'an. Early in this quest, Muslim scribes discovered that the elasticity of Arabic letters, which link together to form cursive words as well as undergo changes in form according to their position at the beginning, middle, or end of a word, allowed for considerable artistic effect. So devoted were the calligraphers, and so beautiful their product, that to write the Qur’an became an act of religious significance.

As one adage sums it up, "The art of calligraphy is hidden in the teaching of a master, much practice is its foundation, and its existence depends on the religion of Islam."

On Oct. 9, the University Art Museums opened the exhibition "Letters in Gold: Ottoman Calligraphy from the Sakip Sabanci Museum, Sabanci University, Istanbul" at the Arthur M. Sackler Museum. The show, which will remain on view through Jan. 2, 2000, features more than 70 works of Ottoman calligraphy, dating from the 15th through the early 20th centuries, and illustrates the development of the art through several devoted masters and apprentices, including Seyh Hamdullah, Ahmed Karahisari, Hafiz Osman, and Sami Efendi.

Origins of Ottoman Calligraphy

Islamic calligraphy has a long tradition, with examples, such as a mosaic band decorating the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, dating to the seventh century. "Letters in Gold" demonstrates the particularly Ottoman contribution to the venera ble tradition. For in the 15th century, after imitating their predecessors for many years, Ottoman calligraphers in Turkey began to place the early masters under critical scrutiny as they refined and elaborated new methods.

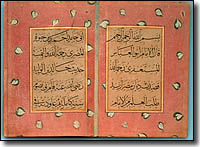

Pages of the sacred Qur'an produced by calligrapher Mehmed Sevki Efendi (1829-1887). |

The exhibit contains two examples of calligraphy by Seyh Hamdullah, the great 15th-century Ottoman innovator who revised the six reigning styles, or scripts, of Yaqut al-Musta`simi, a predecessor who lived in 13th-century Baghdad. Hamdullah's style would shape Ottoman calligraphy for the ensuing centuries. In this exhibit, his handwriting can be seen in a bound Qur'an and in a murakkaa, a type of calligraphic album that was formatted horizontally and mounted in an accordion binding.

Ottoman calligraphers frequently produced bound albums and Qur’ans. However, as the exhibit shows, the artists worked in many formats. There are several examples of kit'a, a type of calligraphic composition typically bordered with marbleized paper and assembled in the album; as well as the levha, a larger panel of pious inspiration meant to hang on a wall. One of the pieces, known as a hilye, is a distinctive type of levha that features a literary portrait of the Prophet Muhammad, done by calligrapher Hasan Riza Efendi in 1905.

In organizing "Letters in Gold," Mary McWilliams, Norma Jean Calderwood Associate Curator of Islamic and Later Indian Art in the University Art Museums, sought to capitalize on the diversity of the collection. "I could have lined everything up chronologically, but that would have diminished each piece," she says. "Instead I asked, how can I use the objects to make some points and pull people in."

McWilliams positioned a selection of documents bearing imperial edicts; grants of imperial title, privilege, or property; and declarations of imperial appointment near the entrance to the gallery. These long scrolls, which were never meant to be framed or displayed in museums, have a dual value today. As McWilliams says, "In the gallery, this is where a visitor is thinking, who are the Ottomans? The objects help to answer that question as well as function as art."

On the other hand, as McWilliams notes, a number of similar scrolls are exhibited at the back of the gallery whose focus is quite different. One of the pieces is a berat granting property to a vizier, issued in 1575 during the reign of Sultan Murad III. In this example the tugra, a calligraphic emblem of the sultan that is located at the top of all the scrolls, is drawn in lapis lazuli blue and outlined in gold ink. "I lined up a few like this to draw attention to the tugra and compare the development of calligraphy and the illuminator’s art," McWilliams says.

The entire collection was formerly the property of Sakip Sabanci, chairman of the board of directors of Sabanci Holding, and one of the founders of the Haci Omer Sabanci Foundation (VAKSA), which provides educational, cultural, and social services throughout Turkey. The works are on loan from the Sabanci Museum, and are being exhibited in cooperation with the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, with funding by Sabanci Holding/Akbank, Istanbul, Turkey.

Sabanci's Collection Shows Deep Respect for Tradition

The "Letters in Gold" exhibit is drawn from one of the largest collections of Ottoman arts in Turkey and was formerly the property of the Turkish entrepreneur Sakip Sabanci. Sabanci is the chairman of the board of directors of Sabanci Holding, the leading Turkish financial- and industrial-sector conglomerate.

Sabanci visited Harvard earlier this month in preparation for the opening of "Letters in Gold." During his stay, he explained that years ago, he decided to invest in a collection of art that would rival those of his colleagues – but that unlike most private collectors, he wanted his collection to last – intact.

"I did not want to have my collection divided among family members after my passing," he said. "This is the reason I decided to give my collection, my home, my furnishings to the public."

A common calligraphic work is the kit'a, a small rectangle typically composed of two scripts. Compiled into albums called murakkas, they can be assembled like books or accordions. This murakka was produced in 1669 by Hafiz Osman (1642-1690). |

As he testifies, Sabanci has a deep respect for tradition. His collection of calligraphy epitomizes this value. In the introduction to the catalog accompanying "Letters in Gold," Sabanci writes, "Apart from the obvious beauty of Ottoman calligraphy, what most appealed to me is the important relationship between master and apprentice and the infinite capacity of this art to renew itself from one generation to the next."

When the works being exhibited at Harvard return to Istanbul, they will reside at the newly established Sabanci Museum, which is in turn going to be allied with Sabanci University. The works will complement instructional programs at the university, while also providing a platform for the exploration of contemporary Turkish art.

The history of Ottoman calligraphy is a story of an unbroken chain of teachers and students who shaped their art through study and emulation of the works of earlier masters. The Sabanci Museum, a teaching museum modeled after the example of the Harvard University Art Museums, will serve as a permanent resource for countless students and teachers of art, art history, conservation, and related professions.

Companion Exhibit Shows Range of Ottoman Arts

In conjunction with "Letters in Gold," the Sackler Museum is presenting the exhibition "A Grand Legacy: Arts of the Ottoman Empire," which features Ottoman painting, ceramics, textiles and metalwork. It is organized by Rochelle Kessler, assistant curator of Islamic and later Indian art.

In contrast to "Letters in Gold," which is strictly devoted to calligraphy on paper, this exhibit showcases the diversity of modes and materials that engaged Ottoman artisans. Included is a 19th-century Anatolian prayer rug, with its geometric arch framed by lotuses, leaves, and rose ttes; as well as 16th-century tiles from the renowned workshops of Iznik, with their polychromatic ornamentation of rumi scrolls and split palmettes, saz foliage, tulips, and carnations. Because the Ottomans were one of the first Islamic dynasties to appreciate the military value of firearms, the exhibit also includes a pair of percussion pistols, a steel helmet, and a miquelet lock musket made of pattern-welded steel, wood, silver, mother of pearl, enamel, turquoise, and coral.

Diverse as these media are, the art of Ottoman calligraphy makes its imprint on them, as well. Among the textiles featured in "A Grand Legacy" is a 17th-century silk lampas cenotaph cover, decorated with alternating large and small zigzag bands of pious invocations in Arabic script. The calligraphy on this work is prominent and unmistakable.

In some cases, however, locating the calligraphy requires more careful inspection. An Ottoman miniature painting depicting the Prophet Muhammad visited by the angel Gabriel includes two calligraphic inscriptions that form part of the architectural backdrop. Elsewhere, a 19th-century steel and ivory sword is inscribed with a captivating message, written in a small script on the face of the blade. It reads: "Oh heart, be not grateful to ruby lips for your life; for this fickle world, be not grateful to the sultan."

"A Grand Legacy" will be on view through Jan. 2, 2000. Objects exhibited are amassed from the holdings of the University Art Museums and supplemented by loans from public and private collections.

Souce: http://www.hno.harvard.edu/gazette/1999/10.21/ottoman.html