A BRIEF HISTORY OF TURKIC LANGUAGES

The Turkic languages are spoken over a large geographical area in Europe and Asia. It is spoken in the Azeri, the Türkmen, the Tartar, the Uzbek, the Baskurti, the Nogay, the Kyrgyz, the Kazakh, the Yakuti, the Cuvas and other dialects. Turkish belongs to the Altaic branch of the Ural-Altaic family of languages, and thus is closely related to Mongolian, Manchu-Tungus, Korean, and perhaps Japanese. Some scholars have maintained that these resemblances are not fundamental, but rather the result of borrowings, however comparative Altaistic studies in recent years demonstrate that the languages we have listed all go back to a common Ur-Altaic.

Turkish is a very ancient language going back 5500 to 8500 years. It has a phonetic, morphological and syntactic structure, and at the same time it possesses a rich vocabulary. The fundamental features, which distinguish the Ural-Altaic languages from the Indo-European, are as follows:

1. Vowel harmony, a feature of all Ural-Altaic tongues.

2. The absence of gender.

3. Agglutination.

4. Adjectives precede nouns.

5. Verbs come at the end of the sentence.

Written Turkish

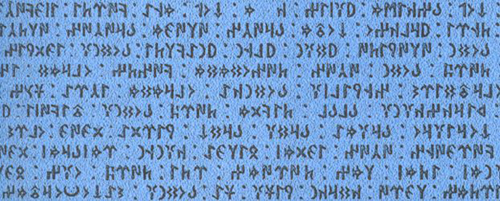

The oldest written records are found upon stone monuments in Central Asia, in the Orhon, Yenisey and Talas regions within the boundaries of present-day Mongolia. These were erected to Bilge Kaghan (735), Kültigin (732), and the vizier Tonyukuk (724-726). These monuments document the social and political life of the Gokturk Dynasty.

After the waning of the Gokturk state, the Uighurs produced many written texts that are among the most important source works for the Turkish language. The Uighurs abandoned shamanism (the original Turkish religion) in favor of Buddhism, Manichaeanism and Brahmanism, and translated the pious and philosophical works into Turkish. Examples are Altun Yaruk, Mautrisimit, Sekiz Yükmek, Huastunift. These are collected in Turkische Turfan-Texte. The Gokturk inscriptions, together with Uighur writings, are in a language called by scholars Old Turkish. This term refers to the Turkish spoken, prior to the conversion to Islam, on the steppes of Mongolia and Tarim basin.

A sample of Gokturk Inscriptions, commissioned by Gokturk Khans. One of several in Mongolia, near river Orkhun, dated 732-735. Example statement (from Bilge Khan): "He (Sky God or "Gok Tanri") is the one who sat me on the throne so that the name of the Turkish Nation would live forever."

The Turkish that developed in Anatolia and Balkans in the times of the Seljuk’s and Ottomans is documented in several literary works prior to the 13th century. The men of letters of the time were, notably, Sultan Veled, the son of Mevlana Celaleddin-i Rumi, Ahmed Fakih, Seyyad Hamza, Yunus Emre, a prominent thinker of the time, and the famed poet, Gulsehri. This Turkish has a dialect which falls into the southwestern dialects of the Western Turkish language family and also into the dialects of the Oguz Türkmen language group. When the Turkish spoken in Turkey is considered in a historical context, it can be classified according to three distinct periods:

1. Old Anatolian Turkish (old Ottoman - between the 13th and the 15th centuries)

2. Ottoman Turkish (from the 16th to the 19th century)

3. 20th century Turkish

The Turkish Language up to the 16th Century With the spread of Islam among the Turks from the 10th century onward, the Turkish language came under heavy influence of Arabic and Persian cultures. The "Divanü-Lügati't-Türk" (1072), the dictionary edited by Kasgarli Mahmut to assist Arabs to learn Turkish, was written in Arabic. In the following century, Edip Ahmet Mahmut Yükneri wrote his book "Atabetü'l-Hakayik", in Eastern Turkish, but the title was in Arabic. All these are indications of the strong influence of the new religion and culture on the Turks and the Turkish language. In spite of the heavy influence of Islam, in texts written in Anatolian Turkish the number of words of foreign origin is minimal. The most important reason for this is that during the period mentioned, effective measures were taken to minimize the influence of other cultures. For example, during the Karahanlilar period there was significant resistance of Turkish against the Arabic and Persian languages. The first masterpiece of the Muslim Turks, "Kutadgu Bilig" by Yusuf Has Hacib, was written in Turkish in 1069. Ali Nevai of the Çagatay Turks defended the superiority of Turkish from various points of view vis-à-vis Persian in his book "Muhakemetül-Lugatein", written in 1498.

During the time of the Anatolian Seljuk’s and Karamanogullari, efforts were made resulting in the acceptance of Turkish as the official language and in the publication of a Turkish dictionary, "Divini Turki", by Sultan Veled (1277). Ahmet Fakih, Seyyat Hamza and Yunus Emre adopted the same attitude in their use of ancient Anatolian Turkish, which was in use till 1299. Moreover, after the emergence of the Ottoman Empire, Sultan Orhan promulgated the first official document of the State, the "Mülkname", in Turkish. In the 14th century, Ahmedi and Kaygusuz Abdal, in the 15th century Süleyman Çelebi and Haci Bayram and in the 16th century Sultan Abdal and Köroglu were the leading poets of their time, pioneering the literary use of Turkish. In 1530, Kadri Efendi of Bergama published the first study of Turkish grammar, "Müyessiretül-Ulum".

The outstanding characteristic in the evolution of the written language during these periods was that terminology of foreign origin was accompanied with the indigenous. Furthermore, during the 14th and 15th centuries translations were made particularly in the fields of medicine, botany, astronomy, mathematics and Islamic studies, which promoted the introduction of a great number of scientific terms of foreign origin into written Turkish, either in their authentic form or with Turkish transcriptions. Scientific treatises made use of both written and vernacular Turkish, but the scientific terms were generally of foreign origin, particularly Arabic.

The Evolution of Turkish since the 16th Century

The mixing of Turkish with foreign words in poetry and science did not last forever. Particularly after the 16th century foreign terms dominated written texts, in fact, some Turkish words disappeared altogether from the written language. In the field of literature, a great passion for creating art work of high quality persuaded the ruling elite to attribute higher value to literary works containing a high proportion of Arabic and Persian vocabulary, which resulted in the domination of foreign elements over Turkish. This development was at its extreme in the literary works originating in the Ottoman court. This trend of royal literature eventually had its impact on folk literature, and folk poets also used numerous foreign words and phrases. The extensive use of Arabic and Persian in science and literature not only influenced the spoken language in the palace and its surroundings, but as time went by, it also persuaded the Ottoman intelligentsia to adopt and utilize a form of palace language heavily reliant on foreign elements. As a result, there came into being two different types of language. One in which foreign elements dominated, and the second was the spoken Turkish used by the public.

From the 16th to the middle of the 19th century, the Turkish used in science and literature was supplemented and enriched by the inclusion of foreign items under the influence of foreign cultures. However, since there was no systematic effort to limit the inclusion of foreign words in the language, too many began to appear. In the mid-19th century, Ottoman Reformation (Tanzimat) enabled a new understanding and approach to linguistic issues to emerge, as in many other matters of social nature. The Turkish community, which had been under the influence of Eastern culture, was exposed to the cultural environment of the West. As a result, ideological developments such as the outcome of reformation and nationalism in the West, began to influence the Turkish community, and thus important changes came into being in the cultural and ideological life of the country.

The most significant characteristic with respect to the Turkish language was the tendency to eliminate foreign vocabulary from Turkish. In the years of the reformation, the number of newspaper, magazines and periodicals increased and accordingly the need to purify the language became apparent. The writing of Namik Kemal, Ali Suavi, Ziya Pasa, Ahmet Mithat Efendi and Semsettin Sami, which appeared in various newspapers, tackled the problem of simplification. Efforts aimed at "Turkification" of the language by scholars like Ziya Gökalp became even more intensive at the beginning of the 20th century. Furthermore, during the reform period of 1839, emphasis was on theoretical linguistics whereas during the second constitutional period it was on the implementation and use of the new trend. Consequently new linguists published successful examples of the purified language in the periodical "Genç Kalemler" (Young Writers).

The Republican Era and Language Reform

With the proclamation of the Republic in 1923 and after the process of national integration in the 1923-1928 period, the subject of adopting a new alphabet became an issue of utmost importance. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk had the Latin alphabet adapted to the Turkish vowel system, believing that to reach the level of contemporary civilization, it was essential to benefit from western culture. The creation of the Turkish Language Society in 1932 was another milestone in the effort to reform the language. The studies of the society, later renamed the Turkish Linguistic Association, concentrated on making use again of authentic Turkish words discovered in linguistic surveys and research and bore fruitful results.

At present, in conformity with the relevant provision of the 1982 Constitution, the Turkish Language Association continues to function within the organizational framework of the Atatürk High Institution of Culture, Language and History. The essential outcome of the developments of the last 50-60 years is that whereas before 1932 the use of authentic Turkish words in written texts was 35-40 percent, this figure has risen to 75-80 percent in recent years. This is concrete proof that Atatürk's language revolution gained the full support of public.

Reference: Ministry of Foreign Affairs/The Republic of Turkey

Some selected references are provided below for further reading.